My 9-year-old was confused when he spotted my copy of Geoffrey K. Pullum’s latest book, The Truth About English Grammar, in our kitchen: “You’re still learning about grammar?” It’s a fair question. I’m well out of school and have spent much of my professional life as an editor.

But yes, I do still brush up on grammar fundamentals once in a while, and Pullum’s slim and pleasant new volume proves a useful way of doing so. It’s brief and readable, yet doesn’t shy away from the maze of technical terms and arcane debates that have plagued every attempt to catalog the rules of our language.

After all, the rules of grammar encompass so much more than the handful of basic concepts and common mistakes most high-school English teachers drill into their students these days. They’re much more complicated than “nouns refer to things and verbs refer to actions.” And for all the anxiety about grammatical errors, native English speakers follow the important rules without even thinking about it — effortlessly constructing sentences that are as intricate as needed to express any given thought.

They could hardly communicate otherwise. As Pullum cheekily puts it, “If I didn’t follow the usual rules of English word order, then figure almost find I saying it out to impossible totally was what would you.” But to know the rules consciously, one has to read books like The Truth About English Grammar every few years.

Pullum, one of the world’s leading linguists, is the man to explain these things. He co-authored The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, a 1,000-page-plus reference work that exhaustively spells out the rules of English, based on extensive analysis of how the language is actually used. It also updates the classification systems presented in what Pullum dubs “traditional” grammars, which range from dusty tomes from centuries ago to the modern authorities influenced by them.

The Truth About English Grammar serves as a sort of on-ramp to this kind of material. There are chapters on familiar topics such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, as well as lesser-known concepts such as “determinatives,” “content clauses,” and “tenseless subordinate clauses.” For each, Pullum offers a rigorous definition, spells out the basic principles — and, as often as not, explains why the traditional grammars don’t get it right.

Newcomers to these topics might be amazed to discover, for instance, that linguists disagree as to what counts as a “preposition,” in a section that nicely illustrates the nerdier joys of the book.

As traditionally conceived, a preposition is basically a short word that goes before a noun and denotes a relationship such as direction, time, or space. (“Get into the car.”) But you sometimes don’t need a noun, a problem traditional grammars handle awkwardly, contending that the preposition morphs into an adverb in such cases, even when it’s obviously the same word being used in the same way. Merriam-Webster’s website will tell you that “down” is a preposition in “fell down the stairs” yet an adverb in “fell down.”

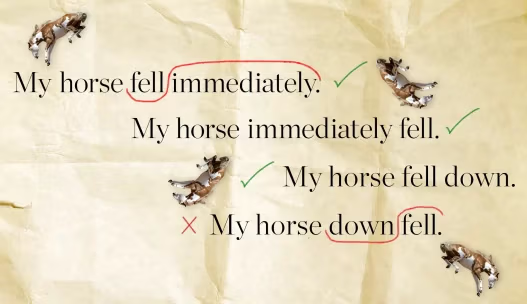

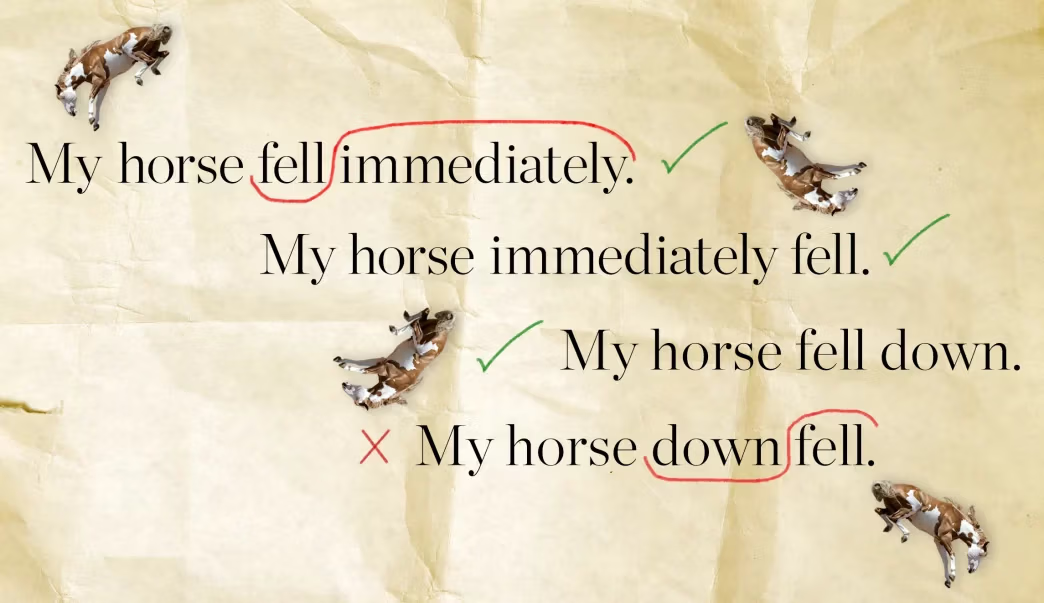

These words, Pullum excitedly reports, “don’t behave anything like adverbs!” For instance, “immediately” is a typical adverb, and in the sentence “My horse fell immediately,” one can move the adverb before the verb (“My horse immediately fell”). But “down” can’t make that shift: “My horse fell down” no longer works as “My horse down fell.”

It thus makes sense to broaden our concept of a preposition, albeit while recognizing that different prepositions have different rules regarding the complements they can or must take. “I took a photo of,” unlike “My horse fell down,” demands a noun to finish the thought, for instance. This makes prepositions similar to verbs, where “Let’s get” is an incomplete thought but “Let’s eat” works, and you can “eat pizza” but not “dine pizza.”

The subtler rules of English can vary word by word, sometimes with a logical explanation (the plural of “focus” is “foci” rather than the expected “focuses,” thanks to a Latin etymological root), but sometimes on a seemingly random basis. This means we can only be grammatical by rote, frustrating any attempt to understand grammar thoroughly in a satisfying way, even as we faithfully implement the rules every time we open our mouths. Pullum notes, for example, that specific adjectives tend to pair with specific prepositions without following any rigorous pattern. We’re proud of, kind to, aghast at, etc., and that’s just the way it is.

Of course, while these sorts of rules have clear right and wrong usage answers, emotions run high with the grammar issues that require judgment, the ones teachers and editors harp on. After all, these are things that everyday English speakers do say but that sticklers see as incorrect. In the book’s later chapters, Pullum offers sensible yet contentious advice on these topics. His pugnaciousness is no surprise: One of Pullum’s best articles for a general audience is his ruthless 2009 evisceration of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, called “50 Years of Stupid Grammar Advice.”

In a chapter called “Mythical Grammar Errors,” he lets loose, defending split infinitives, singular “they” (as in “If someone calls, tell them I’m busy”), introducing sentences with “Hopefully” or “However,” ending sentences with prepositions, and much else. But he’s also pragmatic, pointing out that effective communication requires the appropriate level of formality. Your girlfriend will understand you perfectly well if you text her that you “aint gonna read all that,” but you probably shouldn’t write that way in an academic paper. He also advises readers to go along with teachers’ and editors’ rules even when they’re wrong.

Of course, many of these issues are subjective enough that reasonable people can disagree. For example, in addition to endorsing the use of the singular “they,” Pullum argues against the use of male pronouns in such situations. Whatever the origins of this practice — Pullum contends it started with, interestingly, a female grammarian in the mid-1700s — it has become quite familiar over the years, and sometimes it does sound less awkward than “they,” as in “the reader can decide for himself.” (“Themselves” is probably the best alternative there, though “themself” and “theirself” are also not unheard of.) English doesn’t have a great way to refer to a single person of unknown gender, and perhaps it’s best just to keep our options open.

A similar point holds for his defense of using “which” in integrated relative clauses, as in “a date which will live in infamy.” The prohibition on such constructions was, as Pullum explains, originally made up out of whole cloth by the Fowler brothers in the early 1900s. But sometimes fake rules take hold, and this one did, at least in America. To my millennial American ear, “the horse which won” sounds archaic and a little effete, and usage statistics show a massive decline in such uses of “which” over the past century. It’s not an error, exactly, but it’s best avoided stateside.

Then again, disagreeing with grammar books is half the fun of reading them. The other half comes from learning new things and having a reference on hand for those times when, inevitably, you forget the details and need to look something up. The Truth About English Grammar serves all of these functions impressively well for a book that comes in at less — er, fewer — than 200 pages.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Robert VerBruggen is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

This article was originally published at www.washingtonexaminer.com